My mother, Eileen Pavlic, died on Tuesday, August 6, 2019, due to complications from a stroke. She had been battling cancer for a year, and immunotherapy had been working well to reduce the extent of her cancer. She was enthusiastic about the progress of the treatment and had even started to buy new clothes, anticipating at least another year of life. Then, surprisingly and very sadly, she suffered a stroke. We learned that metastatic cancer is a risk factor for stroke, and so this outcome was not a complete surprise to the doctors even though it was devastating to us. She was buried in an outfit that she had recently ordered and had never had the opportunity to wear herself.

We know she was very impressed and encouraged with the immunotherapy she received, and so I hope you will consider donating to the Pelotonia Institute for Immuno-Oncology (PIIO) or another reputable charity advancing the use of immunotherapy for the treatment and possible cure for cancer.

I shared the comments below during her funeral on August 9, 2019. You can also read her obituary on-line.

A Son's Tribute to His Mother, Eileen M. Pavlic (September 22, 1942 – August 6, 2019)

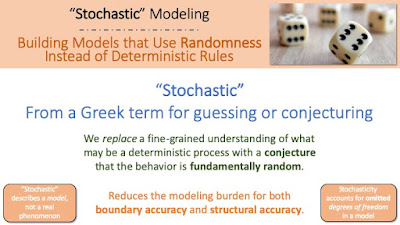

Looking back on your life with someone is less like watching a movie from beginning to end but more like drawing lottery balls from a tumbling urn. There’s one random memory. Then another. Then another. It is only after drawing enough of them that we can look back on them, sort them out, and start seeing hints of a bigger picture. That’s how it was for me when thinking about what to say today, and I only hope this story comes across a little smoother than those lottery balls.

She always wanted me to become a medical doctor, and I was excited to oblige when I was younger. Books and models mom and dad would get me about anatomy and physiology were interesting to me, but ultimately, I think the real source of the appeal was not the content so much as the connection with her. At some point, I pivoted away from medicine toward things like mathematics, computing, and, ultimately, engineering. Even mom might not see how this has anything to do with her, but from my perspective looking back, I remember the young me watching her navigate a DOS prompt, manipulate revealed codes in WordPerfect documents, and designing merge fields for office automation, and she became my model for someone who could learn to use tools around her to do great things. She never viewed herself as a teacher – she would often excuse herself from philosophical discussions that dad and I would have by saying that “she didn’t go to college” – but she was one of my greatest teachers. Today, I teach college students, and I only hope that some of them could be as motivated by me as I was by her. And it’s no surprise to me that biology has shown up in a lot of my engineering research, which sometimes makes me think that the younger version of me is still trying to turn my PhD into an MD to make mom proud.

So, yeah, looking back on life with mom is a little like drawing lottery balls. And by giving me the opportunity to do so, mom’s given me one last lesson – that being her son was winning the jackpot.